On the East Coast, Midwest, and Mountain West, we often hear stories of the pristine old growth temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest, a magical, untouched realm only accessible via the remote lens of social media. These lands of ancient giants steeped in moss and lichen are presented in stark contrast to both the barren landscapes of the rest of the West and the human-warped treescapes of the East. The stories presented, however, are a bit of a fairy tale, a sheen that glosses over the messy truths of human impact on these unique landscapes. If you want to see the entirety of the forest in its present state, go not to the protected Hoh Rainforest or the lands of old giant cedars. Go to the local town forests and the lands of logging operations. Stand in those lands and imagine that once they might have looked more like the protected spaces. Contemplate where they are in their recovery, and how far they have to go. Imagine the hectares of land that are still being lost near Seattle despite protection efforts, and understand that 6 foot wide conifers will never stand where they once stood again. It’s a deep, immeasurable thought space, to read the entire forested landscape.

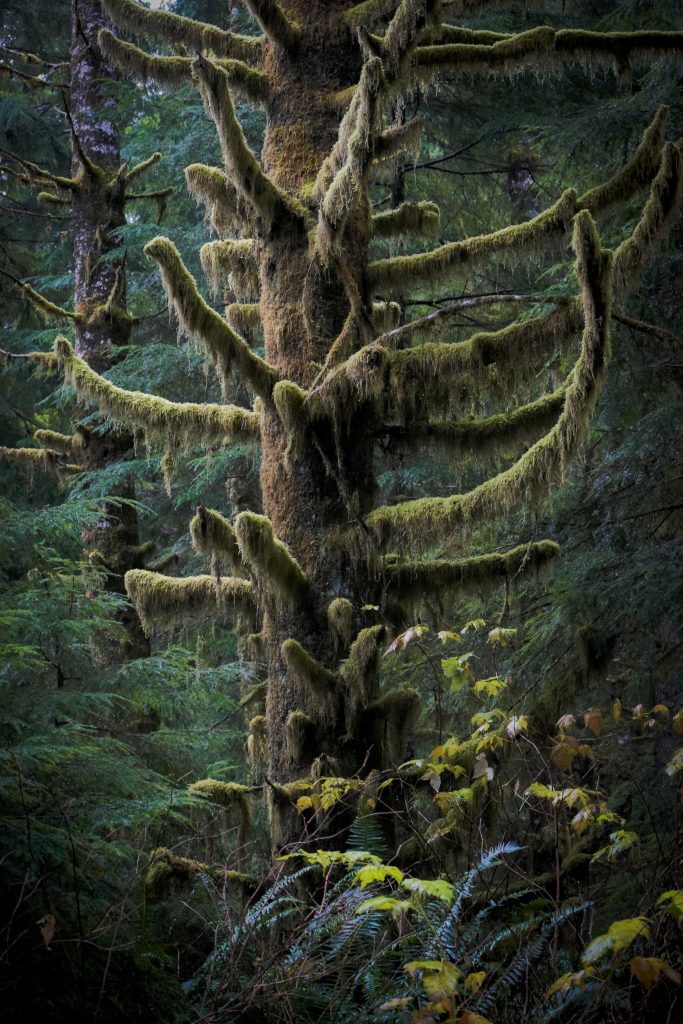

On a recent trip out to Seattle with no real agenda, other than to visit some folks, see the city a bit and hopefully get some outdoor time in, this is exactly what I ended up doing, standing in these half baked forests as they attempted to return to form. Regardless of their state, I was still amazed. This was still a rainforest of a kind I had never seen before. The combination of massive ferns, draping lichens, and a heavy conifer canopy created a combination that is just uncanny to most of us, because it exists nowhere else in the country, and frankly almost nowhere else in the world. To understand why this is, we have to take a look at where these temporate rainforests tend to occur.

Temperate rainforests are often much more limited in range than their tropical counterparts, and they only tend to exist on the Northwestern edges of continents in the northern hemisphere. Another prominent example of a temperate rainforest biome is the United Kingdom, which we don’t often think of as rainforest because its forests have been so heavily decimated by human activity over millennia (and actually served as a counter example for the United States when it was developing its own conservation programs). Both the Pacific Northwest and the United Kingdom are unnaturally warm and rainy for the same reason: ocean currents. In the northern hemisphere, ocean currents run counter clockwise, meaning that when the current is at its lowest and warmest, it begins to travel northwest, bringing all that hot water with it and warming up the terrestrial climate, ultimately turning what would be a snowy, cold place into something that sees much more rain than snow. This phenomenon explains the mossy nature of the place, but it doesn’t explain the dominance of conifer trees in the region.

To explain the conifer trees, we need to look at the overall temperature fluctuations in the Pacific Ocean. While in the winter the current brings warm water up to the coast, in the summer, the water is actually cooler than the surrounding air, creating a cooling effect in the summer. Many types of evergreens are adapted to cooler temperatures and don’t thrive in very hot environments. They are also adapted to periodic drought conditions, which can make life difficult for broadleaf trees. Oddly, summers in the Pacific Northwest are exceptionally dry compared to the rainy winter season. This occurs due to a seasonal shift of the atmospheric phenomenon known as the Hadley Cell, which tends to push dry atmospheric air into the region. This dry season is the only opportunity broadleaves have to extract solar energy with their leaves, but their leaves also rely on moisture in order to function properly. Thus, we see hardwoods widely outcompeted by conifers in this area, and where they do appear, they tend to be early succession species that are quickly replaced in the forest development process.

During our west coast adventure, we saw this heavy proportion of conifers even in the regrowth areas. However, many of them were actually planted species to replace the prior clearcuts done by loggers in the past. On land that was likely an old agricultural zone, as well as in logging areas seemingly left to regrow on their own, we did see a higher proportion of hardwood species, particularly bigleaf maple. The old logging areas we discovered were near Spada Lake in the North Cascade region, but were mostly no longer being used for clearcutting purposes, as the area has become more desirable for recreational usage in recent years. The scale of these trees looked about as you would expect an older, perhaps 100 year old managed forest to look in the eastern US, but the trees that were dated by sign were only 40 years old! Quite young for such long lived species as western hemlock and western red cedar, and given a few examples we encountered in the valleys, likely to get much bigger if the competition thins out over time. These replanted forests stood at the foot of incredibly steep Alp-like mountain slopes, which only occasionally showed themselves through the dense, low-lying clouds of late November. Snow mostly seemed to only accumulate near the tops of the mountains, with low-lying areas remaining a wet, muddy rainforest.

Given the prior research discussed, visiting this area is likely quite different depending on the time of year. Be prepared for mud and rainy, drizzly conditions from fall through spring. Summer will be less likely to rain, but wildfire smoke from the rain shadow regions becomes more likely during this time of year. In late November, the conservation areas around Spada Lake were virtually empty of other people, leaving the conifers to silently experience their fastest growing season of the year.